Sometimes nature tricks us in ways we never expect. We know that many plants use bright colors or sweet smells to invite insects to visit their flowers. But some plants use more surprising methods.

In Japan, there is a small plant called Vincetoxicum nakaianum that does something very unusual. Instead of smelling sweet, it smells like an injured ant. Certain flies that love to eat hurt ants quickly fly toward the scent, hoping for food.

Instead, they end up pollinating the plant. The plant gives the flies nothing, yet it gets exactly the help it needs. How clever can nature be? Well, let’s look at this cool thing.

How the Discovery Happened

The story began when a researcher named Ko Mochizuki noticed something strange in a greenhouse in Tokyo. He was not studying this plant at first. In fact, he was working on a completely different project.

But one day, he saw a group of small flies gathering around a plant that had no bright petals, no sweet nectar, and nothing special to offer. The plant looked simple and plain, yet the flies seemed extremely interested in it. This made him pause and take a closer look.

Mochizuki had collected the plant earlier only for comparison work. It was not meant to be a main part of his research. But now, watching the flies, he felt something was different. These flies usually go to places where they can find injured insects to eat. So why were they landing on this flower?

What made this moment possible was Mochizuki’s earlier training. In 2019, he had taken a difficult course that taught him how to identify many kinds of flies. He had also spent years reading studies about insects and the flowers they visit. Because of this background, he could immediately sense that something special was happening.

His training, his experience, and this unexpected moment came together at the same time. What he saw in the greenhouse sparked a sudden idea in his mind: maybe the plant was pretending to be an injured insect.

This idea pushed him to start observing carefully. It reminded him that sometimes important discoveries begin with small, simple moments when someone decides to look more closely at nature.

Testing the Theory

After forming his idea, Mochizuki needed to test it step by step. He watched which insects came to the flowers and checked if their visits matched his theory. Then he started studying the smell of the plant to see what chemicals it released.

He compared this smell with the smell of different insects. To his surprise, the plant’s scent was almost the same as the smell released by ants when they are injured by spiders.

There was one problem, though. No research had ever said that these flies eat injured ants. To solve this, he began searching for real examples. He looked through online posts from nature lovers who often record insect behavior.

There, he found photos and videos showing spiders attacking ants while small flies gathered around to steal the injured insects. This matched his idea perfectly. These flies were “kleptoparasitic,” meaning they steal food when other animals are hunting it.

To be sure, lab tests were done. Scientists mixed five different chemicals found in the plant’s scent and checked how flies reacted. The flies moved quickly toward the mixture, proving that the smell attracted them.

When either decyl acetate or methyl 6-methyl salicylate was removed, the flies were no longer interested. This meant the plant needed all the right chemicals in the right amounts to successfully fool the flies.

To complete the test, scientists compared the smell of injured ants with the smell of the flowers. They matched almost exactly!

Floral Deception

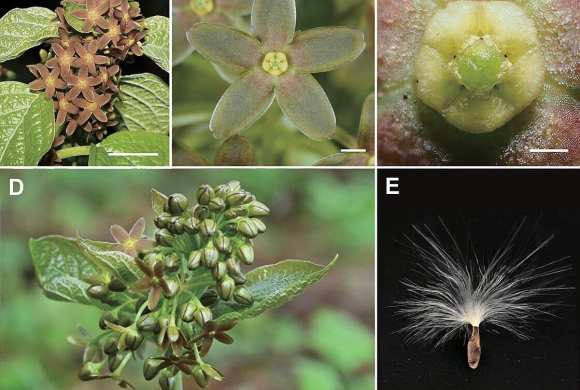

This plant is the first known example of a flower copying the smell of an injured ant. It is a very advanced form of mimicry. This discovery helps us understand how tricky and creative plants can be when it comes to reproduction.

Many plants use deception, but most of them rely on visual tricks. They might look like another insect, or look like something sweet or safe. But this plant uses smell, and not just any smell, it uses the scent of danger.

Deception in plants is actually more common than people expect. Thousands of flowering plants fool insects every day. Many orchids do this. They look like female insects so that male insects will land on them. Other plants pretend to offer nectar even though they give nothing at all. For these plants, tricking insects is a way to survive and keep producing seeds.

What makes this case special is the role ants play. Ants are everywhere. Many animals copy ants to protect themselves or to hunt better. But copying the smell of an ant that has just been attacked is something far more detailed. It shows that plants can develop very sharp strategies to make their survival more certain.

The flies visit because they think they will find food or a place to lay eggs. They touch the flower while searching and end up carrying pollen from one flower to another. They leave with nothing. No nectar. No real injured ant to eat. But the plant gets what it wants: a way to keep living through the next generation. It is a quiet trick, but it works beautifully.

What This Discovery Means

This finding opens new doors for how we understand nature. It shows that plants are doing many things scientists still do not fully understand. If one plant can copy the smell of an injured ant, there may be many others using similar hidden tricks.

These strategies might be happening in forests, fields, or mountains without anyone noticing yet. Mochizuki hopes to keep exploring this area and wants to study how this ability evolved in the plant. He also wants to look for other plants that might use scent mimicry.

Understanding these tricks is important for more than just scientific curiosity. Plants and insects depend on each other. If we destroy their habitats, we may break relationships that took millions of years to develop.

This knowledge can help guide conservation work, especially now when many natural places are shrinking because of human activity.

Sources:

Leave a Reply