In recent years, extreme storms and flooding have moved from being rare disasters to recurring realities. Hurricanes, flash floods, and prolonged rainfall now affect regions that once experienced relatively stable conditions.

These events destroy homes, infrastructure, and crops, but they also quietly devastate something far less visible and equally essential: bee colonies. When hives are submerged, entire populations can be wiped out in hours.

The loss extends beyond beekeepers. Pollination services disappear, ecosystems destabilize, and food systems become more fragile.

Like horror movie, you might want to learn more about it for the plot. Well, we still have the hope of happy ending, but do we really work on it?

Flooding and Bees

Bees evolved to survive predators, parasites, and seasonal changes, but flooding presents a challenge that even healthy colonies cannot overcome. Traditional hives sit directly on the ground.

When heavy rain or storm surges arrive, water fills the hive, drowns the bees, and contaminates stored honey and larvae. Recovery is impossible once a colony is lost. This problem has grown alongside climate change.

Warmer oceans fuel stronger storms, while altered rainfall patterns increase the likelihood of sudden flooding. Agricultural regions, where most managed hives are located, often sit near rivers or irrigation systems. These landscapes offer abundant flowering crops, but they also place bees directly in flood-prone zones.

The scale of the issue is significant. Pollinators support more than one-third of global agricultural production, and bees account for the vast majority of that work. In economic terms, honeybees contribute billions of dollars each year in crop value.

When floods destroy hives, the impact ripples outward. Farmers lose yields, food prices rise, and ecosystems lose a key stabilizing force. What makes this crisis particularly troubling is that it is not caused by disease or natural decline alone. It is intensified by infrastructure that has not adapted to a changing climate.

Floating Protection

The idea behind the Beekon hive began with a simple observation. If water is the problem, then buoyancy can be the solution. Konrad Borowski, trained in mechanical and systems design, approached the issue as an engineering failure rather than an ecological mystery.

Traditional wooden hives were designed for a stable climate that no longer exists. Updating that design became the central goal. The Beekon hive replaces rigid wooden boxes with a modular structure made from recycled plastic.

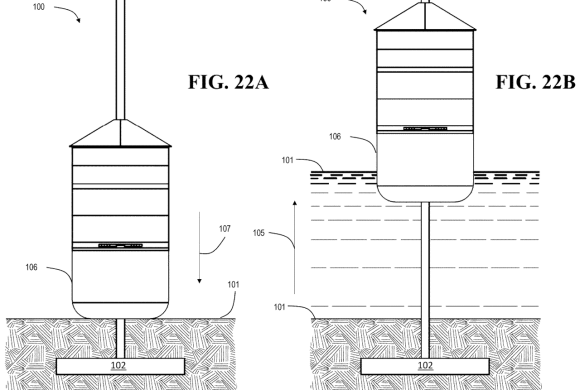

At its core is a central mast anchored securely into the ground. Surrounding it is a buoyant ring that supports the hive body. When flooding occurs, the hive rises along the mast, staying above the waterline. When water levels fall, the hive settles back into place without human intervention.

This design matters because it removes the need for emergency action. Beekeepers cannot always reach their hives during storms, and relocating colonies at short notice is costly and stressful for bees. Elevation platforms help in minor floods, but they fail during severe events. A self-activating system reduces risk while allowing bees to remain in familiar territory.

Equally important is material choice. Plastic does not absorb moisture in the same way wood does, which reduces the growth of fungi and parasites that thrive in damp conditions. The hive does not claim to solve every threat bees face, but it addresses one increasingly common cause of colony collapse in a direct and practical way.

Infrastructure and Conversation

Discussions about saving bees often focus on planting flowers, banning pesticides, or protecting wild habitats. These actions are essential, but they overlook a critical point. Pollination is not an abstract process. It is a service supported by physical systems. Hives, transport networks, and management practices all determine whether bees can survive long enough to do their work.

Modern agriculture depends on managed pollination. Crops bloom on fixed schedules, and bees are moved across regions to meet demand. This system assumes stability. Flooding breaks that assumption. When hives fail, entire regions can lose pollination capacity in a single season.

The decline of bee populations adds urgency. Studies show sharp reductions in both bee abundance and species diversity over recent decades. Habitat loss, pesticide exposure, parasites, and climate stress interact in complex ways. Flooding acts as a force multiplier. A weakened colony might survive disease or heat stress, but it cannot survive drowning.

From this perspective, climate-resilient hive design becomes a form of conservation infrastructure. It does not replace habitat protection or policy reform. Instead, it buys time. It allows colonies to survive extreme events while broader environmental solutions are pursued. Just as flood defenses protect cities, adaptive hives protect the biological workers that underpin food systems.

Scalable Solutions

One of the strengths of the Beekon concept is scalability. The design relies on widely available materials and does not require complex technology once installed.

This makes it suitable not only for industrial beekeeping, but also for small-scale farmers in vulnerable regions. Floodplains, riverbanks, and coastal areas could support pollination without exposing bees to constant risk.

There have been setbacks. Funding interruptions and delayed pilot programs highlight how innovation depends on stable support. Still, the broader idea remains sound. As climate impacts intensify, adaptation will become as important as mitigation.

Protecting bees will require both reducing environmental harm and redesigning the systems that support them.

Other innovations point in the same direction. Nutritional supplements for bees can help colonies survive periods when flowers are scarce after floods or droughts.

Improved monitoring can identify vulnerable regions before disasters strike. None of these solutions work alone, but together they form a toolkit for resilience.

The story of flood-resistant hives offers a useful lesson. Climate change creates new problems, but it also exposes outdated assumptions. Bees are not failing nature. Human systems are failing to keep pace with environmental change.

Updating those systems does not require radical technology. It requires careful observation, practical design, and a willingness to rethink what has long been considered standard.

Sources:

Leave a Reply